发布时间:2021-12-21 15:48浏览数:228评论数:0 收藏

成就目标动机理论是有关学习者在学习中所设定的学习目标,以及设立这种学习目标的理由和原因的理论。成就目标可能会对学习者学业成果和学习过程产生(如学习投入、学业情绪、交际意愿以及语言习得的宽度和广度)产生影响(Lee & Bong,2019)。虽然教育领域的研究广泛证明了成就目标动机的重要作用,然而在应用语言学领域这一理论的运用还没有得到充分的重视(Turner et al.,2021)。

本期“热点聚焦”栏目聚焦两篇中国外语学习环境中的相关文献节选。第一项研究探讨了成就目标对外语学习者自我效能感和自主学习能力的影响,第二项研究探讨了语言学习者成就目标与成就动机、自我效能感、交际意愿以及课堂发言频率之间的关系,并分析了中国文化在这些个体差异中的作用。

两项研究所使用的成就目标动机理论框架和量表分别是成就目标动机的三维框架(Elliot & Church,1997)和四维框架及量表(Elliot & Murayama,2008),这两个理论框架和量表均属经典之作,至今依然被广大学者广泛运用。为此,在展示上述两项实证研究之前,下文首先对相关理论发展进行简要介绍。

Achievement goals examine the motivation behind achievement-seeking behaviors and focus on the innate purposes that drive an individual to achieve (Miller, 2019). One of the most popular framework was the 2*2 achievement goal framework, proposed by Elliot and his colleagues (Elliot & McGregor, 2001; Elliot & Murayama, 2008). According to this model, achievement goals can be categorized into mastery and performance goals, which are based on the definition of competence that is applied (i.e., whether competence is defined in an intra-individual manner by applying absolute standards or an interindividual manner by applying normative standards), and approach and avoidance goals, which are determined by the valence of competence (i.e., whether competence represents the positive possibility of approaching success or the negative possibility of avoiding failure).

The theory has been evolving in two directions. For one, it further distinguishes among the absolute (task), intrapersonal (self), and interpersonal (other) competence. Therefore, the 2*2 model was further expanded into a 3*2 framework (Elliot, Murayama, & Pekrun, 2011). For the other, it proposes a new higher-order construct that integrated the self-determination and achievement goal theory, i.e., the “achievement goal complex”. This new construct probes further into the reasons underlying achievement goals, and argues that the same achievement goal undergirded by different reasons (autonomous or controlled reasons) would lead to different consequences (Liem & Elliot, 2018; Turner, Li et al., 2021).

——北京科技大学 李斑斑

![]() 李斑斑

专家简介

李斑斑

专家简介

基于成就目标定向理论及相关研究,该文提出五项研究假设:

H1:学习目标定向对自我效能感和英语自主学习能力具有显著正向影响。

H2:成绩回避目标定向对自我效能感和英语自主学习能力具有显著负向影响。

H3:成绩接近目标定向对自我效能感和英语自主学习能力具有显著正向影响。

H4:自我效能感对英语自主学习能力存在显著的正向影响。

H5-1:自我效能感在学习目标定向和英语自主学习能力之间起到中介作用。

H5-2:自我效能感在成绩回避目标定向和英语自主学习能力之间起到中介作用。

H5-3:自我效能感在成绩接近目标和英语自主学习能力之间起到中介作用。

研究结果及相关讨论如下:

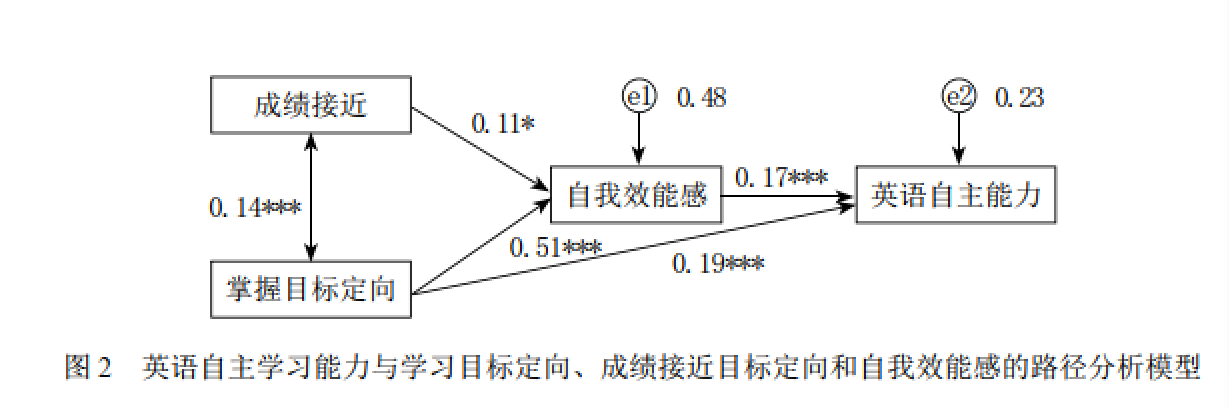

5.1 学习目标定向对英语自主学习能力的影响及自我效能感的中介作用

回归分析和路径分析结果表明学习目标定向对自我效能感和英语自主学习能力产生显著正向影响;自我效能感对英语自主学习能力产生显著正向影响,并在学习目标定向和英语自主学习能力之间产生部分中介作用。这一结果再次验证了前人的一致观点,即学习目标定向对学习的积极的影响(Linnenbrink,2005;Gehlbach,2006等),但是这种积极影响受到自我效能感的影响。学习目标定向的学生会更多地选择挑战性任务,具有较高的自我效能感(Elliott & Dweck,1988;Bell &Kozlowski,2002等),为了掌握英语,他们系统地安排学习计划,选择更有挑战性的学习任务,更倾向于自主管理自己的学习,监控自己的学习过程;然而掌握目标定向的学习者在以掌握英语为目标的学习过程中,在受到挫折或者受到其他因素影响后自我效能感下降的情况下,则可能会在面对挑战时产生迟疑,变得焦虑,怀疑自己的能力,从而降低学习目标定向对英语自主学习能力的影响力。

5.2 成绩接近目标对英语自主学习能力的影响及自我效能感的中介作用

成绩接近目标定向对自我效能感和英语自主学习能力产生显著正向影响,这一研究发现验证了对成绩接近目标定向产生积极影响的学者的观点(如Barron & Harackiewicz,2001;Elliot & McGregor,2001)。自我效能感在成绩接近目标和英语自主学习能力之间产生完全中介作用,这说明成绩接近目标虽然不以学习为目标,但是他们想要表现自己的能力,会非常努力去超越他人,在超越他人的过程中,他们的自我效能感会随之提高。具有高自我效能感的成绩接近目标定向学习者英语自主学习能力也会相应比较高。然而一旦这些成绩接近目标定向的学习者经历了失败挫折,对自己的能力产生怀疑,自我效能感降低时,成绩接近目标定向对英语自主学习能力的预测作用也随之消失。这也再次证明成绩接近目标定向虽然存在潜在的积极作用,但其作用不够稳定。有研究发现成绩接近目标定向与高水平的焦虑、混乱的学习策略使用等消极的学习行为不相关(Elliot & McGregor,2001;Senko & Miles,2008),同时也与那些和学习目标定向相关的积极学习行为,例如对课程的兴趣、灵活的寻求帮助以及共享解决问题的方法等也不相关(Darnon et al.,2006等)。本研究结果给予该现象一些启示,成绩接近目标定向对这些积极或消极的学习行为的影响,可能由于受到了自我效能感的完全中介而消失。

5.3 成绩回避目标定向对英语自主学习能力的影响及自我效能感的中介作用

成绩回避目标定向对自我效能感产生显著负向影响,这一发现与前人研究结果一致(Elliot & McGregor,2001;Harackiewicz et al.,2002;Pintrich et al.,2003)。这说明长期持成绩回避目标定向的学生一直采用回避的态度,避免犯错误,避免表现出无能,不会冒险或挑战自己,他们对学习能力的自信心也会显著下降。在本研究中成绩回避目标定向不对英语自主学习能力产生显著影响。尽管如此,这种消极的成绩回避目标定向以及随之带来的自我效能感的降低会产生其他诸多不良影响,如已有许多研究证明成绩回避目标定向与高水平的焦虑、混乱的学习策略使用等消极的学习行为紧密相关(Elliot & McGregor,2001;Senko & Miles,2008)。

另外相关分析和路径分析结果显示,学习目标定向和成绩接近目标定向之间存在显著的相关关系,说明学习者可以同时具备多种目标定向方式,且学习目标定向和成绩接近目标定向之间可能存在交互作用,Hofmann & Strickland(1995)曾经指出这种交互作用会影响个体的工作绩效与工作满意度。Pintrich(2000)研究发现高学习目标定向和高成绩接近目标定向学习者对任务价值,包括学习兴趣比其他组具有更高的水平。对于学习目标定向和成绩接近目标定向对英语自主学习能力以及自我效能感的交互作用有待未来研究。

摘自:李斑斑、徐锦芬,成就目标定向对英语自主学习能力的影响及自我效能感的中介作用,《中国外语》,2014第5期,第59-68页。

Jeannine E. Turner 专家简介

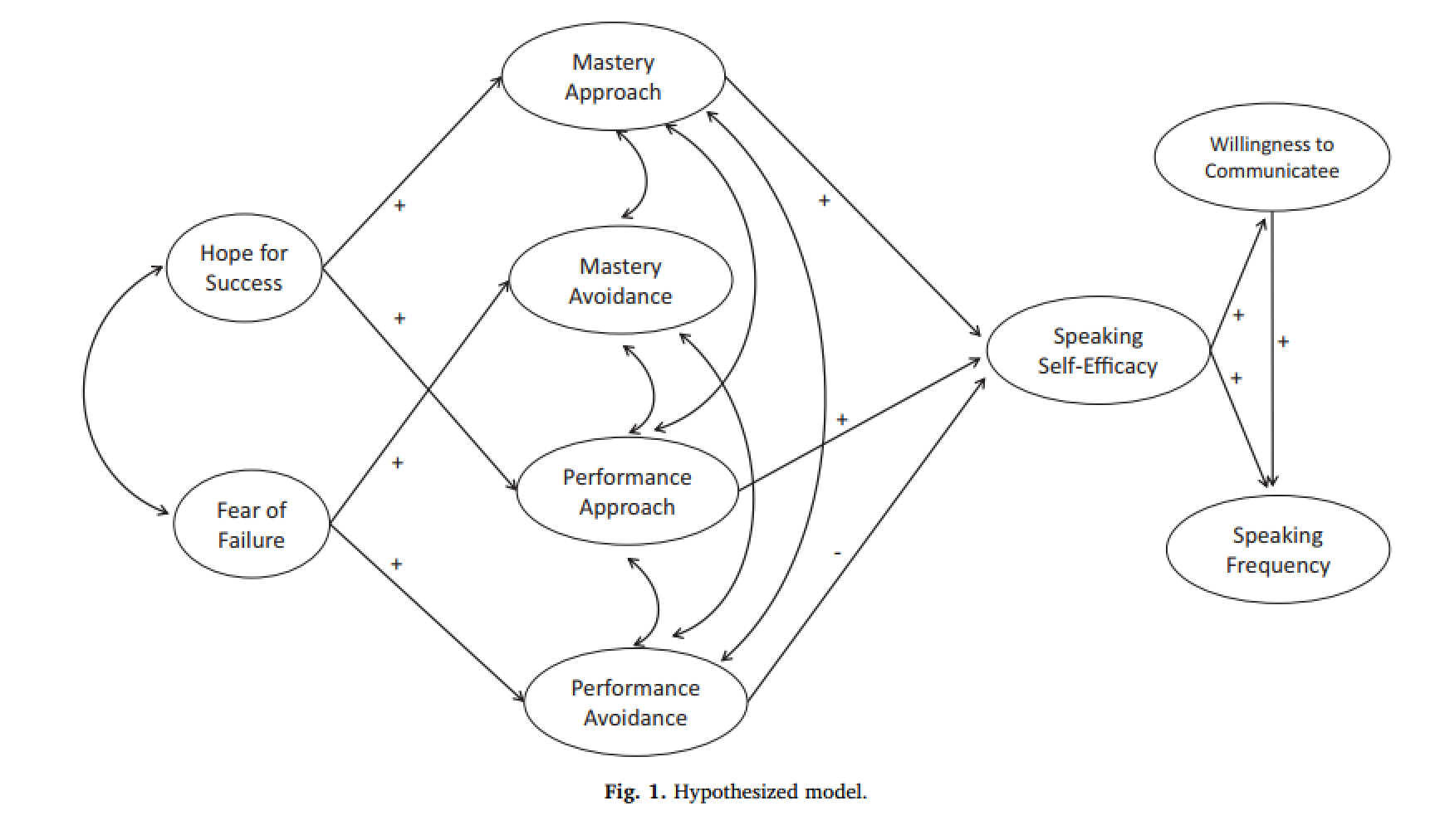

In this study, based on relevant theoretical framework and literature, we developed the hypothesized model, shown in Fig. 1, to guide our analysis. Following previous studies, we anticipated that students' hope for success would be positively related to their approach-focused achievement goals (i.e., mastery approach, performance approach), while fear of failure would be positively related to their avoidance-focused achievement goals (i.e., mastery avoidance, performance avoidance). Furthermore, we expect that students' achievement goals would be related to their levels of speaking self-efficacy, with approach goals positively relating to speaking self-efficacy and performance avoidance goals negatively relating to speaking self-efficacy. Because less is known about mastery avoidance goals, we did not predict a relationship between mastery avoidance goals and speaking self-efficacy. Finally, we anticipated that students' higher levels of foreign-language speaking self-efficacy would be directly related to higher levels of (1) willingness to communicate (which would, in turn, positively relate to speaking-frequency), and (2) self-reported speaking-frequency (see Fig. 1).

5. Discussion

In spite of some limitations, our findings provide insight into ways that Chinese students’ desires to succeed and/or their fears of failing relate to their achievement goals and their efficacy, willingness, and frequency for conducting a skill that is both difficult and public. The underlying assumption is that culture supplies the background in which motives and goal-choices operate (Liem & Elliot, 2018). Our path analysis supported the general assumptions about relationships of motives and goals, and were aligned with previous research (e.g., Bjørnebekk et al., 2013; Elliot & Murayama, 2008). However, we also obtained results that were not in our hypothesized model that may highlight how these variables are impacted within cultural considerations. As we explain below, we believe our data-driven model is supported by propositions within Snyder’s Hope Theory (Snyder, 2002; Snyder, Irving, & Anderson, 1991), as well as Covington and Omelich’s (1991) two-dimensional model of achievement motives (Covington, 1992; Covington & Omelich, 1991). We also proposed that future research should take a student-centered approach, as opposed to a variable-centered approach (e.g., Hiver & Al-Hoorie, 2018), for understanding cultural differences of students’ achievement-related motives, goals, and associated emotions and behaviors. For more detailed discussion, please refer to the paper.

5.8. Conclusions and implications

Our results provide initial insight for understanding Chinese students’ reasons, goals, and classroom-engagement by understanding their motives and goal hierarchies; however, more research is needed. In our research, we particularly focused on foreign language-learning students’ explicit self-attributed motives (as opposed to unconscious implicit motives), that are amendable to change (Conroy, 2017). If college-level instructors want all students to engage with the execution of public skills, such as foreign-language speaking, they need to address some students’ inherent fear of failure/shame, that has developed through a long history of intense pressure to perform at high levels and a long history of receiving rewards or condemnations tied to high-stakes performance-assessments.

To begin, instructors can provide students with multiple pathways to attain success and scaffold students’ use of (1) self-regulation strategies (i.e., planning and monitoring learning), (2) multiple learning strategies (Griffiths, 2015), and (3) metacognitive skills (Efklides, 2011). Teachers could also consider using instructional approaches that provide students with emotional scaffolding in ways that promote their skills and efficacy. Rosiek (2003) defined emotional scaffolding as “scaffolding designed to influence students’ emotional response to an idea” (pg. 401), while Meyer and Turner (2007) defined emotional scaffolding as, “temporary but reliable teacher-initiated interactions that support students’ positive emotional experiences to achieve a variety of classroom goals” (pg. 244). For example, teachers could stress the benefits of speaking in class and provide emotional scaffolding for students to respond positively to the idea of speaking in class. Additionally, instructors need to provide emotional scaffolding to support students’ emotional experiences, such as when speaking in class. For example, teachers can offer low-stakes opportunities for students to speak in class, such as asking simple questions with simple answers or allowing students to speak with a peer before providing public speech, and provide positive feedback. The opportunities for speaking can then become “larger,” such as asking students to provide answers to comprehension-questions. As students become more comfortable with executing skills such as public speaking through scaffolded opportunities, more complex tasks, such as class discussions can become possible (Xing & Turner, 2020). According to Meyer and Turner (2007), emotional scaffolding begins with developing a positive classroom climate that downplays errors and supports risk-taking; whereby, students build trusting relationships with the teacher and their classroom peers. When this happens, “Emotional scaffolding can help to establish and sustain positive relationships and classroom climate[s] that support student engagement, learning, and perceptions of competence” (pg. 248).

Although goals of high performance may predominate within the Chinese cultural setting, providing students with emotional scaffolding may bolster their mastery-focus and self-efficacy, which could increase their initiative for risk-taking and challenge-seeking. Perhaps, through positive emotional experiences, cycles of fear of failure/shame, low-efficacy, performance avoidance, and low engagement can be curtailed. With a better understanding of students’ complex dynamics—including relationships of students’ goal hierarchies and goal complexes (e.g., Liem & Elliot, 2018), along with their self-efficacy, self-regulation, engagement, and emotional responses to feedback—researchers can provide teachers with nuanced ways to support students’ motivation, positive emotions, engagement, and ultimate accomplishments in difficult learning-endeavors, such as speaking a foreign language within the classroom.

摘自:Jeannine E. Turner, Banban Li & Maipeng Wei. (2021). Exploring effects of culture on students’ achievement motives and goals, self-efficacy, and willingness for public performances: The case of Chinese students’ speaking English in class. Learning and Individual Differences, 85.